ExpressVPN blog

Your destination for privacy news, how-to guides, and the latest on our VPN tech

Latest Posts

-

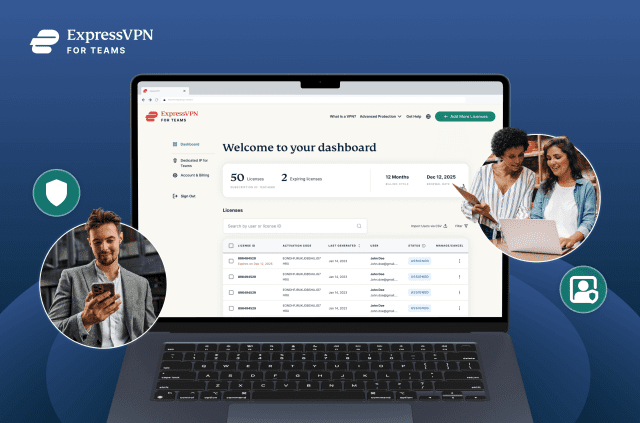

What ExpressVPN looks like when teams start using it

ExpressVPN for Teams is an upgrade to ExpressVPN’s previous volume licensing, aimed at small and growing teams. It introduces centralized admin controls, so access and licenses can be managed in one...

-

How to set up a static IP address (step-by-step)

If you need to consistently reach a device, such as a gaming server or a smart-home hub, you don't want its IP address to change in the background. Assigning a static IP gives it a permanent location ...

-

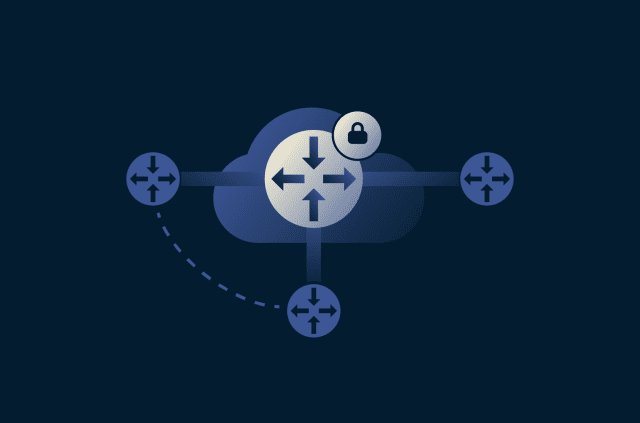

What is encrypted DNS, and why does it matter?

Every time you visit a website, your device asks a Domain Name System (DNS) server to find the website's IP address. But here’s the catch: traditional DNS requests travel in plaintext, so anyone int...

Featured

See allFeatured Video

-

Top 10 video games that will change how you view privacy

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7uOfHGT5p4w If you love online gaming and are interested in privacy, check out these video games that involve hacking, cybersecurity, and surveillance. Not only ...